Senior Care: Driving for Seniors

Can a person be too old to drive?

Can a person be too old to drive?

The answer to this question is not clear-cut and not one that should be applied across the board to all seniors. Nonetheless, with the current growth in our aging population we need to seriously review current and future policies on driving as they apply to seniors. As a community and society, we need to better understand the challenges / barriers and step in to mitigate. Policy review and changes is not something that affects seniors… it will affect our selves in the coming years. This is a delicate balance as we attempt to protect society from senior drivers we also need to ensure that we protect their rights and inevitably, our own rights as a senior citizen. Statistically speaking: Next to young male drivers, people aged 70 or older have highest accident rate

The New Retirement: In a recent, CBC News presented a series on life for people 60 years and older. Canadians Seniors are living longer than ever before, a fact that is radically changing the meaning of retirement. Many people see it as a time of reinvention, a time to try new things. CBC News is published stories on seniors who are doing remarkable things in the so-called twilight years. In one instance, a police officer pulled over a driver for driving too slow and impeding traffic. The officer glanced at the driver’s license and saw her age — 94 — and explained he wasn’t going to give her a ticket. But a couple of weeks later, she said she received a letter notifying her that her license was suspended for medical reasons.

“Never thought of not having a car, never crossed my mind,” explained Ellison. “When you can’t go out and get in your car and go where you want to go, it’s like having your arm cut off.”

According to the latest figures from Statistics Canada, three-quarters of Canadians aged 65 and older have a driver’s license. But research also shows that the older a person is, the greater risk they are on the road. StatsCan reports that other than young male drivers, people aged 70 or older have the highest accident rate. Furthermore, seniors are much more likely to be killed in collisions.

The loss of a driver’s license can affect quality of life:

Those statistics don’t change the fact that once a person loses their license, it greatly affects their lifestyle and overall mental health. “It’s been demonstrated and said many times, that receiving the news that you will be losing your driver’s license has the same weight as being diagnosed with cancer,” said Sylvain Gagnon, a researcher for the Canadian Driving Research Initiative for Vehicular Safety in the Elderly (CANDRIVE). He explained the news of losing your license, can often be followed by depression and a significant loss in quality of life. Figures show that access to a car affects a person’s social habits. StatsCan found that seniors who primarily travelled via their car were the most likely to have partaken in a social activity in the past week, at 73 per cent. The StatsCan research shows that seniors who depend on others to get around are more likely to be reluctant when asking to attend leisure activities (rather than essential activities, like doctor’s appointments). Since losing her license, Ellison must now rely on her daughters and friends for transportation to her personal and social errands.

Life without wheels:

The loss of a license may be even more detrimental for seniors living outside urban areas. According to StatsCan, people aged 65-74 are slightly more likely to live outside urban areas. Of those seniors, a large number reportedly do not use transit because of a lack of service in their area, which may only further immobilize them.

According to Ellison, if you are out in the country and don’t drive, “you just might as well be dead”. — Peggy Ellison, Ontario Senior .

Ellison was 21 when she first got her license. She went on to two driving-related jobs, including parking cars at a garage and driving a bus for 20 years. She said that in the seven decades that she had a license, she was never in an accident. “I haven’t changed because I got old, at least I don’t think I have,” said Ellison. It is estimated that people make eight to 12 navigating decisions for every kilometre they drive. According to the Ontario Ministry of Transportation, even small changes as a result of aging can affect your driving. In Ontario, a person’s driver’s license can be suspended if a doctor or optometrist feels a person has a condition that may impair their ability to drive. Doctors are bound by law to report this condition to the Ministry of Transportation, which then reviews the information and acts accordingly. A doctor may take into account a number of factors when assessing a senior’s ability to drive, including vision, mobility and cognitive abilities. “You will never be able to tell in a doctor’s office whether someone is safe to drive,” said Gagnon, who is also a psychology professor at the University of Ottawa. Gagnon explained driving is a complex task, and there is no one single indicator of a driver’s competence. A doctor can only hope to narrow down the grey area of who is safe to drive. CANDRIVE is currently trying to come up with an instrument that could be used by doctors to assess older drivers.

Renewal process for seniors:

In the meantime, some provinces require that drivers be retested once they reach a certain age. For instance, in Ontario at the age of 80, drivers must renew their license and continue to do so every two years. They complete a vision test, a written test and sit in on a group education session. They may also be required to take a road test. In provinces such as Alberta, a driver needs to take a medical exam at the age 75, and again at 80 and every two years after that. Doctors are not required by law to report seniors who they believe are unfit to drive. However, the province has other safety measures in place. For instance, when drivers renew their license they have an obligation to disclose whether they have a medical condition that would affect their ability to drive. In Alberta, anyone can request that someone’s driving privileges be reviewed if they suspect that person is becoming a danger on the road. Trent Bancarz, a spokesperson for Alberta Transportation, said the majority of the requests probably come from family members. “If you do have someone in your family that either due to age or due to a medical condition is maybe not a safe person to be out there, it’s really hard to either confront them or to take their driving privileges away,” said Bancarz. But he said there should be no age bias involved with the decision to take away someone’s license. “Some people are better able to drive a vehicle at 82 then some other people at 45,” Bancarz said.

Seniors forced to change lifestyle:

Gagnon warned the recommendation to take away someone’s license should not be made lightly, because of the dramatic impact it can have on a person’s life. How a senior reacts to the news that he or she can no longer drive may depend on a number of factors, including a senior’s autonomy, how far away they are from their services and what the alternate transportation methods are.

The day after Peggy Ellison sold her Buick to a young man in town, she took out the Yellow Pages with the intention of buying a golf cart, a four-wheeled vehicle that doesn’t require a license. Her new ride was delivered to her home the next day. “There’s nothing like having a car,” Ellison says, “but it makes me feel a little bit of independence again since I got my cart. I love to have wheels.

This year, more than 3.5 million drivers over 65 will strike out on Canadian roads – the highest number in history. That fact is fuelling a simmering debate over whether Canada’s provinces ought to have tougher licensing criteria for elderly drivers. Most provinces require drivers aged 80 and up to renew their license and take a written test every two years. None have mandatory in-car driver tests. However, on a per-kilometre basis, seniors are the most collision-prone operators on the road. They are also subject to some of the highest insurance rates, on par with the rates levied on newly licensed young males. The problem with those statistics, experts argue, is that they belie much of the grey that muddies the senior driving issue. “The mere fact that you are old doesn’t mean you have a problem,” said Dr. Jamie Dow, the medical adviser on road safety for the Société de l’assurance automobile du Quebec, a crown corporation responsible for licensing drivers and vehicles. “The fact that you are older does make you more susceptible to having a problem.” Public health data supports this.

In 2010, two thirds of Canadians over the age of 65 were using multiple medications and nearly nine out of 10 suffered from a chronic condition; a quarter of adults in the 65 to 79 age group suffered four or more chronic conditions. In the over 80 year old group, the number jumped to more than a third, according to data from the Public Health Agency of Canada. “There is clearly a strong association between age and illness,” said Bonnie Dobbs, and Edmonton-based gerontologist who helms the Medically At-Risk Drivers’ Centre at the University of Alberta, a research centred devoted to studying the impact of medical conditions on driving. “Age is not the primary determiner of fitness to drive. [But] as we get older, we’re more likely to have one or more of the illnesses that can impact our ability to drive.” Nellemarie Hyde, an occupational therapist and program co-ordinator for Saint Elizabeth Driver Assessment and Training service in Ontario, regularly evaluates senior drivers with medical illnesses. The most common are diabetes, which can impact both vision and sensory function – think ability to gauge force on gas or brake pedals – Parkinson’s Disease with its hallmark physical tremors, stroke victims and people living with dementia and other mild cognitive impairments. “Mild memory deficits don’t necessarily affect driving directly,” she said, adding that she focuses more on a driver’s ability to concentrate, focus and multi-task. She also tests for strength, range of motion, co-ordination, sensation and visual perception. “We want the client to be able to continue driving safely,” she said, adding: “The challenge is when a medical condition starts to change how they drive.” Picking up on that condition is where policy makers struggle.

In most provinces, doctors are legally mandated to inform licensing bodies when they suspect a patient is no longer competent to drive. However, most doctors are “totally unprepared to do it,” said Dow. “Most physicians have no training in evaluating drivers or the effects of medical conditions on driving,” he said, adding the subject is rarely touched on by medical schools. The result is that some provinces are deluged with declarations from physicians. In other cases, physicians barely report at all. Several efforts are under way to provide physicians with tools to easily and efficiently identify medically at-risk drivers without risking discrimination by age. Through the SAAQ in Quebec, Dow runs free seminars for doctors on which exam observations ought to trigger red, road-related flags. Last year, Quebec recorded 16,000 physician declarations, compared with just 1,800 in 2003. In Ontario, Shawn Marshall, an Ottawa-based rehab medicine specialist, is near the end of a five-year, multi-province study called CanDrive, which follows 1,000 drivers over the age of 65 and aims to produce an even more accurate tool. “You want to have a screening tool that is valid, reliable and has high accuracy. You don’t want to identify people falsely,” he said, noting it strains provincial systems and unfairly restricts individuals who belong on the road. “The average 65-year-old is a healthy person,” he said. “Driving is important. To maintain your independence in many places throughout Canada, you need to be able to drive.”

How Does Age Affect Driving?

More and more older drivers are on the roads these days. It’s important to know that getting older doesn’t automatically turn people into bad drivers. Many of us continue to be good, safe drivers as we age. But there are changes that can affect driving skills as we age.

Changes to our Bodies: Over time your joints may get stiff and your muscles weaken. It can be harder to move your head to look back, quickly turn the steering wheel, or safely hit the brakes. Your eyesight and hearing may change, too. As you get older, you need more light to see things. Also, glare from the sun, oncoming headlights, or other street-lights may trouble you more than before. The area you can see around you (called peripheral vision) may become narrower. The vision problems from eye diseases such as cataracts, macular degeneration, or glaucoma can also affect your driving ability. You may also find that your reflexes are getting slower. Or, your attention span may shorten. Maybe it’s harder for you to do two things at once. These are all normal changes, but they can affect your driving skills. Some older people have conditions like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) that change their thinking and behavior. People with AD may forget familiar routes or even how to drive safely. They become more likely to make driving mistakes, and they have more “close calls” than other drivers. However, people in the early stages of AD may be able to keep driving for a while. Caregivers should watch their driving over time. As the disease worsens, it will affect driving ability. Doctors can help you decide whether it’s safe for the person with AD to keep driving.

Other Health Changes: While health problems can affect driving at any age, some occur more often as we get older. For example, arthritis, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes may make it harder to drive. People who are depressed may become distracted while driving. The effects of a stroke or even lack of sleep can also cause driving problems. Devices such as an automatic defibrillator or pacemaker might cause an irregular heartbeat or dizziness, which can make driving dangerous.

Smart Driving Tips

Planning before you leave:

- Plan to drive on streets you know.

- Limit your trips to places that are easy to get to and close to home.

- Take routes that let you avoid risky spots like ramps and left turns.

- Add extra time for travel if driving conditions are bad.

- Don’t drive when you are stressed or tired.

While you are driving:

- Always wear your seat belt.

- Stay off the cell phone.

- Avoid distractions such as listening to the radio or having conversations.

- Leave a big space, at least two car lengths, between your car and the one in front of you. If you are driving at higher speeds or if the weather is bad, leave even more space between you and the next car.

- Make sure there is enough space behind you. (Hint: if someone follows you too closely, slow down so that the person will pass you.)

- Use your rear window defroster to keep the back window clear at all times.

- Keep your headlights on at all times.

Car safety:

- Drive a car with features that make driving easier, such as power steering, power brakes, automatic transmission, and large mirrors.

- Drive a car with air bags.

- Check your windshield wiper blades often and replace them when needed.

- Keep your headlights clean and aligned.

- Think about getting hand controls for the accelerator and brakes if you have leg problems.

Driving skills: Take a driving refresher class every few years. (Hint: Some car insurance companies lower your bill when you pass this type of class. Check with AARP, AAA, or local private driving schools to find a class near you.)

Medicine Side Effects: Some medicines can make it harder for you to drive safely. These medicines include sleep aids, anti-depression drugs, antihistamines for allergies and colds, strong pain-killers, and diabetes medications. If you take one or more of these or other medicines, talk to your doctor about how they might affect your driving.

Am I a safe driver? Maybe you already know of some driving situations that are hard for you–nights, highways, rush hours, or bad weather. If so, try to change your driving habits to avoid them. Other hints? Older drivers are most at risk when yielding the right of way, turning (especially making left turns), changing lanes, passing, and using expressway ramps. Pay special attention at those times.

Is It Time to Give Up Driving? We all age differently. For this reason, there is no way to say what age should be the upper limit for driving. So, how do you know if you should stop driving?

To help you decide, ask:

- Do other drivers often honk at me?

- Have I had some accidents, even “fender benders”?

- Do I get lost, even on roads I know?

- Do cars or people walking seem to appear out of nowhere?

- Have family, friends, or my doctor said they are worried about my driving?

Am I driving less these days because I am not as sure about my driving as I used to be? If you answered yes to any of these questions, you should think seriously about whether or not you are still a safe driver. If you answered no to all these questions, don’t forget to have your eyes and ears checked regularly. Talk to your doctor about any changes to your health that could affect your ability to drive safely.

How Will I Get Around? You can stay active and do the things you like to do, even if you decide to give up driving. There may be more options for getting around than you think. Some areas offer low-cost bus or taxi service for older people. Some also have carpools or other transportation on request. Religious and civic groups sometimes have volunteers who take seniors where they want to go. Your local Agency on Aging has information about transportation services in your area.

If you still have a vehicle consider a companion service that will keep you company as needed and provide you with a driving service, to and from where you need to go. In Our Care – Home Care Services can do that, its effective, inexpensive, convenient and safe.

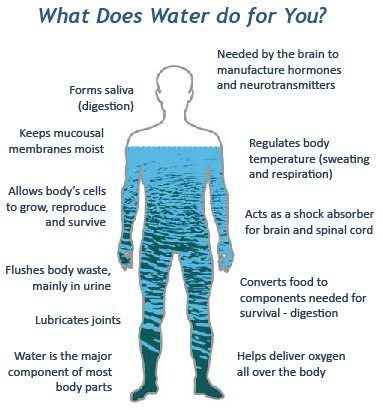

Why should I drink water?

Why should I drink water?

The fact that aspartame is NOT a dieter’s best friend has been known by scientists for some time. The problem is this news has not received the necessary traction in the media. For example, a study from 19861, which included nearly 80,000 women, found that those who used artificial sweeteners were significantly more likely than non-users to gain weight over time, regardless of initial weight. According to the authors, the results “were not explicable by differences in food consumption patterns,” and concluded that:“ The data do not support the hypothesis that long-term artificial sweetener use either helps weight loss or prevents weight gain.”

The fact that aspartame is NOT a dieter’s best friend has been known by scientists for some time. The problem is this news has not received the necessary traction in the media. For example, a study from 19861, which included nearly 80,000 women, found that those who used artificial sweeteners were significantly more likely than non-users to gain weight over time, regardless of initial weight. According to the authors, the results “were not explicable by differences in food consumption patterns,” and concluded that:“ The data do not support the hypothesis that long-term artificial sweetener use either helps weight loss or prevents weight gain.”