Elder Abuse – Have you heard about it?

Know it, Report it, Stop it!

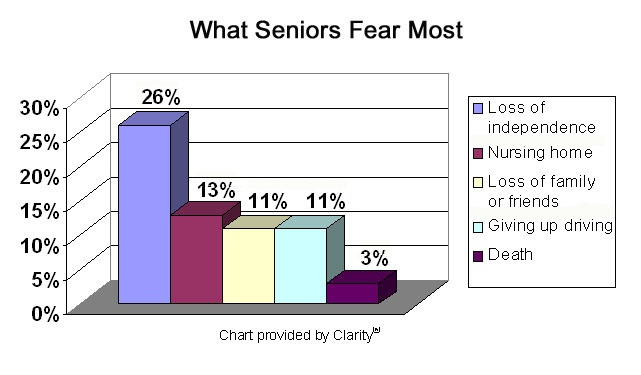

Canada’s population demographics is shift, the number of seniors in Canada has increasing by 57.6% between 1992 and 2012. Within the same period, the number of children dropped by 3.6%. This shift hypotheses that an increasing number of people will be put into a position of caregiver for their parents/grandparents even as they are caregivers to their own families. Juggling these dual care giving roles & responsibilities can bring on a great deal of stress, anxiety, and despair.

While no one underestimates the level of responsibility, accountability and stress levels associated with caregiving, caring for an older senior can present a number of new challenges. Caring for an adult is much different than caring for child yet the level of patience and compassion required must be the same. An untrained person can easily become overwhelmed with the demands required to effectively manage, care for, and delivered care… in a caring manner. With that being said, there’s a real potential for frustration levels to escalate, setting the stage for elder abuse. Unfortunately, it does not happen quite like that. If that were the case, it would be so easy to intervene and resolve it. Elder abuse is far more complex and widespread than just the physical abuse. Not to say that it does not begin there.

So. What is Elder Abuse?

Although elder abuse includes the types of behaviours attributed to domestic violence, it also includes additional types of abuse such as neglect and financial exploitation. It also occurs in a wider range of settings and relationships. Perpetrators of elder abuse cases can be spouses but can also be children, grandchildren, other relations, friends, fellow residents in an institution and personal caregivers. Issues related to individual cognitive and physical functioning are central concerns in elder abuse and consequently frail older people have become identified with this perspective.

The World Health Organization defines elder abuse as, “Single or repeated acts, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within a relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person.”

Fast facts:

- Among seniors who’ve been physically abused, 68% report the assault was committed by a family member (Source: Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration)

- 96% of Canadians think most of the abuse experienced by older adults is hidden or goes undetected (Source: Environics poll for Human Resources and Social Development Canada)

- Female seniors (38%) are more likely to be abused than male seniors (18%). (Source: Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration)

Under-reporting

Some studies suggest that women and men differ in their tendency to report abuse and may interpret questions about abuse differently. For example, women seem to be more willing than men to identify themselves as perpetrators of emotional abuse. However, as is the case in all surveys about sensitive issues, respondents may also be reluctant to disclose their experiences due to shame, fear or lack of trust. Older women may have fewer resources and less independence than men and may be less inclined to report abuse due to fear of leaving their home or accusing someone who provides for their daily needs. Older men, on the other hand, may be embarrassed or ashamed that they are no longer in a position of control in their home. There may be a shift in this with the aging of the baby boomers as the stigma associated with masculine need for help lessens.

There is a huge under-recognition of abuse of seniors in Canada. I would say this field is 20 years behind where we were when we were trying to raise awareness about violence against women and, before that, how to prevent and respond to abuse of children.”

Elder abuse is often referred to as ‘the hidden crime.’ It can take many forms, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial abuse, mental abuse and neglect.

Fortunately, there is no better time than now to tackle the issue because seniors are by far the fastest growing segment of the population. Statistics Canada predicts that by 2026 seniors, aged 65 and older, who now account for 13% of the Canadian population, will grow to 21%.

A closer look at Elder Abuse:

- Elder abuse is an issue that may affect seniors in all walks of life. However, some seniors may be at greater risk of experiencing some type of abuse: those who are older, female, isolated, dependent on others, cared for by someone with an addiction, and seniors living in institutional settings.

- Those who are frail, who have a cognitive impairment or a physical disability.

- In most cases, the person being abused knows and trusts the abuser and relies on him/her in some way, which makes it even worse. It might be a child, another family member, another senior, a fellow resident in an institution, a paid caregiver or even a spouse.

- Unfortunately, seniors can make easy targets. Many live alone and are socially isolated, which increases their vulnerability. Others are dependent on their abuser for care. Some suffer from dementia or other health issues that may prevent them from responding to the abuse or reporting it. Some may feel it’s impossible to get away from the abuser if the relationship has been long standing. And many seniors who simply are not as physically strong as they once were are unable to defend themselves.

Forms of Elder Abuse:

The Ontario Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse (ONPEA) uses the following descriptions:

Financial Abuse – One of the most common forms of elder abuse. It often refers to the theft or misuse of money or property such as household goods, clothes or jewelry. It also includes forcing the sale of property or possessions, misusing power of attorney responsibilities, coercing changes in a will, withholding funds and/or fraud.

Physical Abuse – Is any physical pain or injury that’s willfully inflicted upon a senior. It includes unreasonable confinement or punishment resulting in physical harm, as well as hitting, slapping, pinching, pushing, burning, pulling hair, shaking, physical restraint, physical coercion, forced feeding or withholding physical necessities.

Sexual Abuse – Is any sexual activity that occurs when one or both parties cannot or do not give consent. It includes, but is not limited to, assault, rape, sexual harassment, intercourse, fondling, intimate touching during bathing, exposing oneself, and inappropriate sexual comments.

Psychological (Emotional) Abuse – Is the willful infliction of mental anguish or the provocation of fear of violence or isolation. This kind of abuse diminishes the identity, dignity and self-worth of the senior. It can include name-calling, yelling, ignoring the person, scolding or shouting, insults, threats, intimidation or humiliation, treating as a child, emotional deprivation, isolation, and the removal of decision-making power.

Neglect – Can be intentional or unintentional. It happens when the caregiver of a dependent senior fails to meet his/her needs. Forms of neglect include not providing adequate food, housing, medicine, clothing or physical aids, as well as inadequate hygiene, supervision and safety precautions. It also includes withholding medical services and medications, overmedicating, allowing a senior to live in unsanitary or poorly heated conditions, and denying access to necessary services, such as homemaking, nursing, and social work. For a variety of reasons seniors themselves, may fail to provide adequate care for their own needs, and this is known as self-neglect.

Older women who’ve been abused have been socialized to believe this is not something they’re supposed to talk about. This is a historical problem and their mothers and grandmothers, who may also have also been victims of abuse, probably didn’t talk about it either. To go specifically to an agency that serves abused women is very difficult for them and there’s a stigma attached to it. We need to be able to reach these women wherever they are – and we need to let them know it’s okay to talk about and it’s okay to get some help.

Recognizing the signs of elder abuse

Sometimes it can be difficult to determine if an elder is actually being abused since there may be other explanations for the signs, such as a fall, self-neglect or poor personal choices. Other times it’s more obvious abuse is going on. One thing experts agree on is the longer the abuse goes on, the worse it tends to get.

The following are possible signs an elder is being abused:

Financial Abuse/fraud:

- Significant withdrawals from the elder’s accounts

- Sudden changes in the elder’s financial condition

- Items or cash missing from the senior’s household

- Suspicious changes in wills, power of attorney

- Unpaid bills, even when the elder has enough money to pay

- Financial activity the senior couldn’t have done, such as an ATM withdrawal when the account holder is bedridden

- Unnecessary services, goods, or subscriptions

- Paying far more for work/service than others would be charged

- Large advance payments with nothing to show for it

Physical Abuse:

- Unexplained signs of injury such as bruises, welts, or scars, especially if they appear symmetrically on two sides of the body

- Broken bones, sprains, or dislocations

- Reports of drug overdose or apparent failure to take medication

- Regularly (a prescription has more remaining than it should have)

- Broken eyeglasses or frames

- Signs of being restrained, such as rope marks on wrists

- Caregiver’s refusal to allow you to see the elder alone

Sexual Abuse:

- Bruises around breasts or genitals

- Unexplained venereal disease or genital infections

- Unexplained vaginal or anal bleeding

- Torn, stained, or bloody underclothing

Psychological/Emotional Abuse:

- Threatening, belittling, or controlling caregiver behavior witnessed by others

- Behaviour from the elder that mimics dementia, such as rocking, sucking, or mumbling to oneself

Neglect: (By caregivers and/or self)

- Unusual weight loss, malnutrition, dehydration

- Untreated physical problems, such as bed sores

- Unsanitary living conditions: dirt, bugs, soiled bedding and clothes

- Being left dirty or unbathed

- Unsuitable clothing for the weather

- Unsafe living conditions (no heat or running water; faulty electrical wiring, other fire hazards)

- Desertion of the elder at a public place

Addressing the growing concern over elder abuse

Some jurisdictions have designated resources to deal exclusively with elder abuse.

On April 17, 2009, the Ontario Network for Prevention of Elder Abuse launched a province-wide toll-free hotline for at-risk seniors (1-866-299-1011), which is part of an elder abuse strategy funded by the provincial government at a cost of nearly $900,000 a year.

On June 15, 2009 the Government of Canada launched a nation-wide elder abuse awareness campaign, including an advertising campaign dubbed Elder Abuse – It’s Time to Face the Reality. The 2008 federal budget also earmarked $13 million over three years to help seniors and others recognize the signs and symptoms of elder abuse and to provide information on available supports.

The challenges in detecting and preventing elder abuse in long-term care facilities and retirement homes are compounded by the number of people providing care, the often high ratio of residents to workers, the various cognitive and physical impairments of residents, and by the demands and expectations of family members. Enhanced non-abuse training and increased staffing levels are critical to minimizing the chances of elder abuse occurring.

The Bill of Rights for People Living in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes was published in September 2008 by the Advocacy Centre for the Elder and Community Legal Education Ontario. It outlines 19 fundamental rights for long-term care residents and most long-term care facilities post these rights so staff, residents and family members are all aware of them. Knowing these rights is especially important given the increasing number of media reports about elder abuse in institutions.

Most of the cases of elder abuse that are reported to police tend to involve fraud, the most common form of elder abuse.

“To address elder abuse, it is imperative that action take place at the community level and that resources be allocated to this. Participants delivered a unanimous message:

that without adequate and sustainable funding, efforts to combat elder abuse in local communities are compromised.”

Fast facts:

- The greater the impairment of a senior or the more severe the illness, the more likely it is that he/she will be abused. (Source: Canadian Mental Health Association)

- Male seniors (9%) are more likely to report financial or emotional abuse, compared to female seniors (5%). (Source: Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration)

- A study involving 31 nursing homes reported that 36% of nursing home staff had witnessed the physical abuse of an older adult and 81% had witnessed some

form of psychological abuse. (Source: Canadian Mental Health Association)

Risk Factors for Elder Abuse

Some of the risk factors for elder abuse apply to the abuser, others the victim. Caregiver stress, for example, is a key factor in abuse in both the home and in institutional settings. That stress is intensified if the senior has mental health issues or physical care needs the caregiver is incapable of providing. Caring for a senior with multiple needs can be overwhelming and eventually lead to depression.

Even caregivers in institutions can experience stress levels that can lead to abuse. Excessive responsibilities, poor working conditions, long hours and inadequate training can all be contributing factors.

Sometimes family caregivers are poorly informed and lack the education and support required to properly care for an elder at home.

“When it comes to neglect, we see some families who aren’t providing appropriate care for their elderly loved ones, but it’s not necessarily because there’s any ill intent; sometimes it’s because they don’t know how to care for someone who’s sick, debilitated and has Alzheimer’s.”

Other risk factors include a history of family violence. If there has been abusive behaviour within the family in the past, there’s a greater likelihood an elder will be abused at some point in the future.

There are also the personal problems and personalities of the abusers themselves. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, abusers are more likely to have mental health problems, substance abuse issues and/or financial problems.

Signs that a caregiver may be abusing an elder may include:

- Being aggressive, insulting or threatening behaviour

- Speaks for the elder and doesn’t allow him/her to make decisions

- Reluctant to leave the elder alone with a professional.

Signs that an elder may be a victim of abuse:

- Is anxious, withdrawn, agitated, evasive, depressed or suicidal.

- Shows fear of caregiver; behaviour changes when care giver enters/leaves room.

- Is frail or cognitively impaired and presenting for emergency treatment alone or without regular caregiver.

- Has low self-esteem.

Habits:

- Sudden/unexpected change in social habits.

- Sudden/unexpected change in residence or living arrangements.

- Unexplained or sudden inability to pay bills, account withdrawals, changes in his will or Power of Attorney, or disappearance of possessions.

- Refusal to spend money without consulting caregiver.

- Claims of being “accident-prone”.

- Missed/cancelled appointments, especially medical appointments.

Some people say, “I wonder why I’ve never come across a case of physical elder abuse, especially when you know the statistics”. I think this really speaks to the fact that elder abuse is so hidden and it reminds us how vigilant we all need to be in looking for the signs.

Health & Well-Being:

- Sudden/unexpected decline in health or cognitive ability.

- Poor/decline in personal hygiene; skin ulcers.

- Dehydration or malnutrition; sudden/rapid weight loss.

- Signs of over/under-medication.

- Suspicious injuries: bruising in various stages of healing; on the face or eye area, the inner part of the thighs or arms, or around the wrists or ankles.

- Sexually transmitted disease; itching, pain or bleeding in genital area; difficulty sitting or walking.

- Explanation of injury or condition: inappropriate to type/degree; vague or bizarre; conflicting information from elder and care giver.

- Unexplained delay in seeking treatment.

- Denial in view of obvious injury.

- Previous reports of similar injury.

Environment:

- Poor living conditions in comparison to assets.

- Inappropriate or inadequate clothing.

- Lack of food.

- Lack of required medical aids, functional aids, or medications.

- Evidence of locks or restraints.

- Living in worse conditions than others in the home.

- Involuntary separation from others in home, friends or other family members.

Fast Facts:

“Sometimes our role becomes helping the adult children realize their parent still has the ability to make his or her own choices and that they have that right. Just because someone is 80 doesn’t mean they can’t think clearly or make decisions.”

- 12% of Canadians have sought out information about a situation or suspected situation of elder abuse or about elder abuse in general.

(Source: Environics poll for Human Resources and Social Development Canada.)

- There are almost 300,000 seniors living in institutions in Canada. (Source: Statistics Canada)

- Fewer than one in five situations of abuse actually come to the attention of any public agency, and fewer still come to the attention of a public agency operating in the criminal justice system. (Source: Canada’s Aging Population: Seizing the Opportunity, Special Senate Committee on Aging, 2009)

Taking Action: What to do if elder abuse is suspected

It’s a job for police when a crime has been committed under the Criminal Code of Canada. These offences include assault, forcible confinement, sexual assault, extortion, fraud, forgery, theft, (including theft by a person with power of attorney), uttering threats, criminal harassment, criminal negligence and failure to prove the basic necessities of life. If in doubt, people are advised to call police, who will help determine what to do next.

There are no quick fixes or simple solutions in addressing the issue of elder abuse. The challenges in raising awareness, responding to elder abuse and ultimately mitigating and eliminating it are many, but the energy, commitment and expertise already exists among those who have taken on this task across the country.

There is also a toll-free, confidential elder abuse hotline in Ontario that provides information, support and referrals to services 24 hours a day, seven days a week at 1-866-299-1011. In emergency situations dialing 911 is the best option.

Even though there are no legal requirements to report suspected elder abuse of people living in their own private residences, anyone who witnesses harm being done to an elder in a long-term care facility is required by law to report it to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. This can be done by calling the toll-free Action Line at 1-866-434-0144.

“The field of prevention of abuse and neglect of older adults in Canada is lagging behind other areas of family

violence prevention. It is largely the case that multiple small-scale projects and a few noteworthy larger programs exist in a patchwork of service delivery and under- coordinated effort. It is also far from being able to use practice standards that are available for other fields.”

The Canadian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse suggests the following as the best steps to take for seniors who are being abused:

For seniors living in the community:

- Tell someone what’s happening to you.

- Ask others for help if you need it.

- If someone is hurting or threatening you, or if it is not safe where you are, call police.

- Find out more from community resources about your options to take care of your financial security and personal needs.

- Call for counselling and support.

- Make a safety plan in case you have to leave quickly and contact Optimism Place, Victim Services or the Emily Murphy Centre for help developing a plan that’s right for you.

You might also:

- Set aside an extra set of keys, I.D., glasses, bank card, money, address book, medication, and important papers. Keep this outside of your home.

- Find a safe place with friends and family so you have a place to go to in an emergency.

- Consider obtaining a restraining order to protect yourself.

“We believe that when people learn about victims who’ve had the strength to come forward and reach out for help it encourages others to do the same.”

For seniors living in a nursing home or other kind of assisted living facility:

- Tell someone what is happening to you.

- Ask others for help if you need it. Staff members have a responsibility to see that abuse stops and that you get the help you need.

- If someone is hurting or threatening you, or if it is not safe for you where you are, call the police.

“Most people working in Home Care Services, including those in long-term care are in the field because they choose to be. They love the elderly and are committed to their care and wellbeing.

“The elderly in our community need to know it’s okay to ask for help. Too often they’re too nervous or they don’t want to bother the police; they don’t even know if what’s happening to them is a crime. They don’t realize there are other organizations they can turn to for help – and which would put them in contact with the police if need be.”

Talking about the future can be hard. Such discussion will invoke anxiety in even the most calm of us when we start to think about all the unknowns in our futures and those of our loved ones. These discussions can get even harder when it’s not our future we’re talking about, but rather someone else’s. However, as difficult as it may be, there are some questions that we need to have answers to when it comes to our ageing parents and it is wise to have these conversations sooner rather than later. On that note, here are 7 basic questions that you should include in the “talk” with your ageing parent/s… as soon as you can.

Talking about the future can be hard. Such discussion will invoke anxiety in even the most calm of us when we start to think about all the unknowns in our futures and those of our loved ones. These discussions can get even harder when it’s not our future we’re talking about, but rather someone else’s. However, as difficult as it may be, there are some questions that we need to have answers to when it comes to our ageing parents and it is wise to have these conversations sooner rather than later. On that note, here are 7 basic questions that you should include in the “talk” with your ageing parent/s… as soon as you can. Sometimes there’s a lot of pressure to do things in a “traditional” way when it comes to how we remember our loved ones, but that’s not always what they want. Although funerals/memorials need to reflect both the person that is gone and those who are left behind, having a discussion ahead of time can mean that all sides get their voices heard. When a decision is reached beforehand, our loved ones know their wishes will be respected and those of us left behind can know we’re memorializing our parents in a way that they accept as well. This means no guilt for anyone and that’s a much-needed relief at a time of sorrow.

Sometimes there’s a lot of pressure to do things in a “traditional” way when it comes to how we remember our loved ones, but that’s not always what they want. Although funerals/memorials need to reflect both the person that is gone and those who are left behind, having a discussion ahead of time can mean that all sides get their voices heard. When a decision is reached beforehand, our loved ones know their wishes will be respected and those of us left behind can know we’re memorializing our parents in a way that they accept as well. This means no guilt for anyone and that’s a much-needed relief at a time of sorrow.

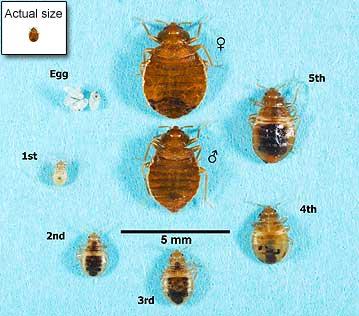

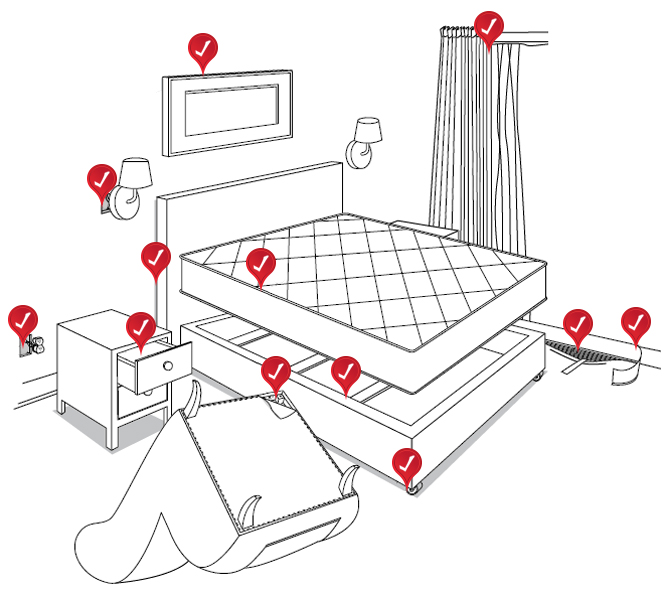

Bedbugs are small, oval, brownish insects that live on the blood of animals or humans. Adult bedbugs have flat bodies about the size of an apple seed. After feeding, however, their bodies swell and are a reddish color.

Bedbugs are small, oval, brownish insects that live on the blood of animals or humans. Adult bedbugs have flat bodies about the size of an apple seed. After feeding, however, their bodies swell and are a reddish color. Bedbugs may enter your home undetected through luggage, clothing, used beds, couches and other items.

Bedbugs may enter your home undetected through luggage, clothing, used beds, couches and other items. Bedbugs are active mainly at night and usually bite people while they are sleeping. They feed by piercing the skin and withdrawing blood through an elongated beak. The bugs feed from three to 10 minutes to become engorged and then crawl away unnoticed.

Bedbugs are active mainly at night and usually bite people while they are sleeping. They feed by piercing the skin and withdrawing blood through an elongated beak. The bugs feed from three to 10 minutes to become engorged and then crawl away unnoticed. This article delves into ageist stereotypes dressed-up in the garb of myth that biases perceptions and experiences of being old. The article argues current ”mythmaking” about aging perpetuates that which it intends to dispel: ageism. It considers how traditional myths and folklore explained personal experience, shapes social life, and offers meaning for the unexplainable. The current myths of aging perform these same functions in our culture; however, they are based on half-truths, false knowledge, and stated as ageist stereotypes about that which is known. Recent studies in the cognitive sciences are reviewed to provide insight about the mind’s inherent ability to construct categories, concepts, and stereotypes as it responds to experience. These normal processes need to be better understood, particularly regarding how social stereotypes are constructed. Finally, the article argues that ageist stereotypes when labeled as ”myth” even in the pursuit of the realities of aging, neither educate the public about the opportunities and challenges of aging nor inform social and health practitioners about the aged.

This article delves into ageist stereotypes dressed-up in the garb of myth that biases perceptions and experiences of being old. The article argues current ”mythmaking” about aging perpetuates that which it intends to dispel: ageism. It considers how traditional myths and folklore explained personal experience, shapes social life, and offers meaning for the unexplainable. The current myths of aging perform these same functions in our culture; however, they are based on half-truths, false knowledge, and stated as ageist stereotypes about that which is known. Recent studies in the cognitive sciences are reviewed to provide insight about the mind’s inherent ability to construct categories, concepts, and stereotypes as it responds to experience. These normal processes need to be better understood, particularly regarding how social stereotypes are constructed. Finally, the article argues that ageist stereotypes when labeled as ”myth” even in the pursuit of the realities of aging, neither educate the public about the opportunities and challenges of aging nor inform social and health practitioners about the aged.

Can a person be too old to drive?

Can a person be too old to drive?

A Summary of Canada’s Aging Population

A Summary of Canada’s Aging Population

If it sounds too good to be true… it probably is not.

If it sounds too good to be true… it probably is not.